As we cross the market place we glance at the church clock, or hear it chiming but, how did it get there?

In 1738 a parish meeting was held in Ilkeston about the purchase of a public clock. At the meeting 5/- (5 shillings – 25p – for those born in more recent years!) was paid for ale, and at the town meeting 3/-.

St Mary’s evidently had a sundial. As the more economical among the ratepayers said “The sun and the old dial and the bell ringing at morn and eve did just as well”.

A neighbouring parish however (probably St Laurence’s at Heanor) had a clock dated 1647, which would be a verge and foliot balance, and this settled the question. In 1739 the clock was duly installed and 5/6d was paid for drink for getting up the dial board. The dial plate itself cost 11/-. A sum of £5 12s 6d was paid to Mr Phillipe towards the clock. This was probably Phillips of Loscoe. In 1740, 3/- was paid for mending the clock hammer and a new spring.

The present clock movement, which is situated behind the dials and approximately half way up the church tower, carries a plate which bears the following inscription:-

“This clock was paid for by public subscription and the following gentlemen formed the committee.

G.B. Norman Esq. M.D. Churchwarden

E.S. Whitehouse Esq. CChurchwarden

W.S. Aldington Esq.

P. Potter Esq.

G. & W. Cope, Makers, Radford, Nottingham, February 1864”

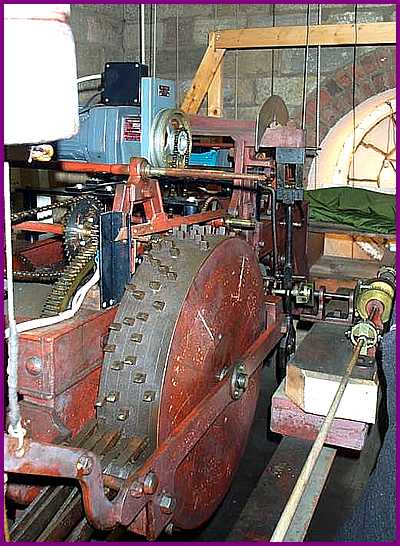

The ‘going train’, or clock mechanism, is driven by a weight which hangs from a wire rope and is automatically re-wound by an electric motor. The motor does not drive the clock, it winds it.

The speed of the clock, in other words it’s timekeeping, is controlled by a pendulum acting through an escapement which produces the ticking sound each time a tooth passes through it. In warm weather, the metal pendulum expands and gets longer and, as a result, the clock slows down and loses slightly. In cold weather, the pendulum contracts and gets shorter, the clock goes more quickly and gains slightly. Normally, the timekeeping is fairly accurate, within half a minute a week, although it can be upset by snow on the hands or mechanical problems.

The mechanism is cleaned and oiled approximately once a year.

The clock is fitted with a Westminster chime which chimes the quarter hours by ringing the church bells with hammers which are lifted by a revolving drum fitted with pegs similar to a musical box. This mechanism is now driven by an electric motor which has replaced the former weight drive. The clock starts the chime by moving a lever every quarter hour and the pegs, on the drum, are arranged to play the bells in the correct sequence.

In addition to the quarter chimes, the clock strikes the hours. A separate mechanism, again powered by an electric motor, which is controlled by the clock and the quarter chime, strikes the appropriate number on a different bell.

Originally, and until the late 1980’s, it was necessary to climb the tower twice weekly to wind up the weights for the clock, chime and strike mechanisms. The electrification, which was carried out by John Smith and Sons of Derby, was designed to eliminate this chore and has safety features built in which enable it to ‘sort itself out’ in the event of a power cut.

The lights which we see from the ground are simply 60watt lamps which hang behind the glass dials. At Christmas they are replaced by red ones to give the seasonal effect.

As the inscription says, this is a public clock and is maintained, and paid for, by the Borough Council. Strictly speaking, St. Mary’s should have nothing to do with it but, in the real world, we do keep an eye, and an ear, on things.

Peter Hodson